Introduction

Basel III is a set of precautionary measures imposed on banks and are made to protect the economy from financial crises similar to that of recent years. Principally they aim to ensure banks accept a level of responsibility for the financial economy they operate within and to act as a safeguard against further collapse.

What is Basel III?

The set of measures known as Basel III were designed with a much broader purpose than merely strengthening the world’s banks. The Basel III reforms arose from the common realisation by the world’s leading politicians, central bankers, business leaders, academics and social organisations that entire national economies and the material well-being of citizens had been put at risk by the high-risk behaviour of a handful of major banking institutions mainly located in USA, Switzerland, UK and some European nations.

They had grown so big relative to the size of their national economies that they had become “too big to fail”. That is, if they were not rescued whatever the cost, their collapse would cause even more severe economic damage through job losses, housing repossessions, reduced GDP and lending of credit than actually occurred. Further, the burden of saving these giant institutions cost ordinary taxpayers heavily.

All these factors combined to trigger what has become known as the Great Recession, the most severe economic crisis in 80 years. Thus Basel III, one of the biggest responses to crisis, is specifically designed to make sure that the banking sector supports and underpins the world’s economies rather than threatens them.

Although at first the industry lobbied aggressively against certain aspects of the Basel III reforms, there’s mounting evidence that it sees the requirements as beneficial in the long term. This is because they enhance the robustness of individual banks while helping rehabilitate the industry’s reputation among the investment community, depositors and law-makers.

Essentially, Basel III and related measures by national and supranational regulators will force the banks to maintain a much bigger capital base – in effect, a foundation stone of solid assets designed to withstand sudden market disruption. In general Basel III will force banks to become smaller relative to the size of their national economies. Lower levels of leverage – the ratio of capital to assets – will become obligatory. And they must have greater stores of spare cash on hand to tide them over temporary difficulties.

The cumulative result is that banks will be forced to adopt a more responsible outlook that reflects on their contribution to society at large as well as to internal goals. For instance, bonuses will only be paid out for longer-term, sustainable performance rather than for short-lived profits. Perhaps most importantly, Basel III outlines that banks small and large have been warned to devise a system for closing their doors without help from taxpayers if they get themselves into trouble.

What are the main principles?

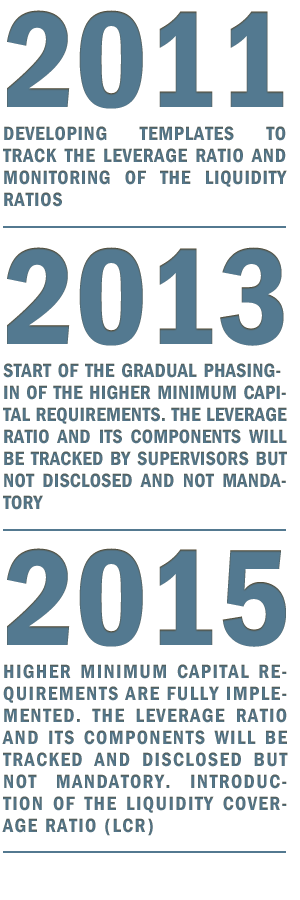

The world’s banking sector is involved in an obligatory flight to quality under the package of reforms known as Basel III designed to eliminate – or at least greatly reduce – the danger of another financial crisis. Produced by the Bank for International Settlements – the “central bankers’ bank” – based in Basel, Switzerland, they are intended to make the world’s banks – and especially the systemically important institutions known as Sifis – stronger and safer. These far-reaching global standards must be fully implemented by 2019.

As the BIS points out, it was the interconnectedness and vulnerability of the sector that precipitated the crisis. “One of the main reasons the economic and financial crisis became so severe was that the banking sectors of many countries had built up excessive on and off-balance sheet leverage,” it says. “This was accompanied by a gradual erosion of the level and quality of the capital base. At the same time, many banks were holding insufficient liquidity buffers. The banking system therefore was not able to absorb the resulting systemic trading and credit losses.”

Overall the purpose of the Basel III package, which was first unveiled in 2010 and modified in late 2011, is to ensure that the financial sector remains in a position to fulfil its primary function of providing credit to individuals and businesses. “The objective of the reforms is to improve the banking sector’s ability to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress, whatever the source, thus reducing the risk of spillover from the financial sector to the real economy,” says the BIS.

Also included in the package is the so-called shadow banking system such as hedge funds, insurance companies and other significant firms that were linked with the front-line banks through often complex and little-understood transactions.

Although highly technical, the principle underlying Basel III is clear and simple. Namely, the financial community is there to serve the broader economic community. “A strong and resilient banking system is the foundation for sustainable economic growth, as banks are at the centre of the credit intermediation process between savers and investors,” Basel III points out. “Banks provide critical services to consumers, small and medium-sized enterprises, large corporate firms and governments who rely on them to conduct their daily business, both at a domestic and international level.”

How will it work?

The detailed provisions of Basel III are purpose-designed to render the financial sector as immune as possible from future upheavals both from within and outside national borders. Thus the new standards are based on microprudential reforms at the level of individual banks and macroprudential reforms across the entire banking sector. And they start with the integrity of their capital base. Individual banks must in future hold more, high-quality capital to protect them against unexpected losses to help them ride through any traumas in the financial markets. These take the form of fatter buffers for capital or equity, cash and liquid assets than were required under Basel III’s predecessor, Basel II which the BIS admits was not tough enough.

There are four main elements in the package.

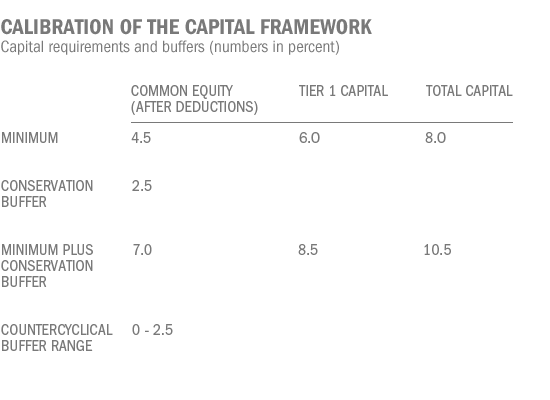

- First, capital. Banks must hold core tier one capital – the highest-quality assets – equal to seven percent of their assets after they’ve been adjusted for risk. The biggest institutions – the so-called systemically important financial banks – must carry an extra 1-2.5 percent in capital, giving them a total of up to 9.5 percent of risk-weighted assets. If they don’t, they face restrictions on the payment of bonuses and dividends that might otherwise affect the firm’s overall integrity. If the bank is thought to be failing or “non-viable”, the capital can be written off or converted to common shares at the discretion of the local regulator. The purpose of this is to force losses on shareholders rather than on taxpayers. Also, a “countercyclical buffer” can be required to further shock-proof a firm. If authorities judge a bank has put itself in danger by lending too much, they can order it to boost common equity by up to 2.5 percent.

- Second, management of risk. Among other measures all banks must conduct much more rigorous analysis of the risk inherent in certain securities such as complex debt packages.

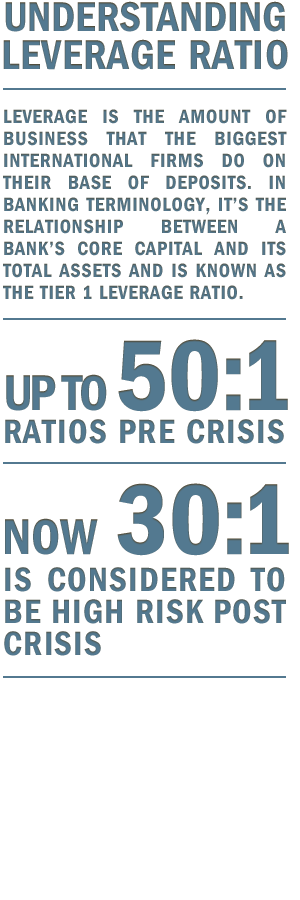

- Third, leverage. Aiming to reduce the ratio of assets that banks, especially the biggest, built up in relation to deposits, Basel III sets much tougher standards than before. In future banks must include off-balance sheet exposures when they measure leverage. The ratio of core tier one capital to a bank’s total assets, with no risk adjustment, may not exceed three percent.

- Fourth, market discipline. To improve the industry’s and shareholders’ understanding of the risks banks may be running, they must make far more complete disclosures than before the crisis. This particularly applies to their exposure to off-balance sheet vehicles, how they are reported in the accounts, and how banks calculate their capital ratios under the new regulations.

What should banks do?

The BIS has concluded that a lack of liquidity was a significant catalyst for the crisis. Thus responding to the speed at which much of the world’s financial sector ran out of spare and especially overnight cash in October 2008, Basel III sets much higher standards for liquidity.

- Cash on hand: Banks must have enough cash and easy-to-sell assets on hand to survive a 30-day crisis in the financial markets, even though the turmoil was caused by outside forces.

- More demanding stress tests: Under new standards banks must retain sufficient high-quality liquid assets to survive a 30-day scenario when its funding comes under pressure whether through its own or others’ actions.

- More reliable funding: To avoid an excessive reliance on short-term financing that is vulnerable to abrupt changes in the markets, Basel III established a new net stable funding ratio designed to meet any mismatches in a firm’s liquidity profile. Thus a bank’s obligations are carefully compared with its sources of financing.

- Monitoring standards: To help bank supervisors analyse the status of a bank’s liquidity, Basel III has drawn up an industry-wide set of measurements known as “monitoring metrics”. Once again, the systemically significant banks whose failure is deemed to be particularly dangerous will be required to “gold-plate” their liquidity ratios. Still a work in progress, the purpose of the metrics is to increase their capacity to absorb losses without endangering the rest of the banking community.

- Quarantining sick banks: A main element of the package is a system for shutting down crippled large banks in a way that prevents them from contaminating the rest of the banking community. Known as the resolution process, it affects mainly cross-border banks.

What should banks not do?

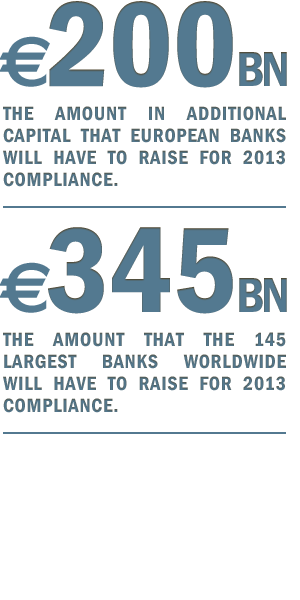

The architects of Basel III have not denied that compliance with its provisions imposes unique and significant but unavoidable burdens on banks. With the first steps to be implemented in 2013, the introduction of Basel III has triggered a rush towards compliance. According to a study of the status of European banks by Boston Consulting Group, they will have to raise nearly €200bn in new capital or face the likelihood of having to cut their balance sheets by nearly 20 percent. In total, the 145 largest banks worldwide in Europe, USA, Asia and Latin America and elsewhere must find an extra €354bn more than they had at the end of 2010, the study concludes.

The stark alternative is to reduce risk-weighted assets by €5trn equivalent to 17 percent, thus significantly diminishing the size of the bank. The generally higher capitalised banks in the United States and Asia are in a better position with less than €70bn to raise.

Banks have lobbied against some aspects of the reforms, arguing that some of the capital and liquidity requirements are too severe. They say the requirements may force them to reduce their ability to provide credit to industry and may result in an increase in costs to customers because they tie up large amounts of low-yielding capital in regulatory buffers. An industry body, the Washington-based Institute for International Finance calculates that borrowing costs for customers may have to rise by 3.5 percent.

And although “endorsing the goals and objectives” of Basel III, the institute fears the measures as they stand could cut global output by 3.2 percent by 2015 and cost 7.5 million jobs. However regulators reply their own studies of the impact of Basel III show it would reduce growth by only a small increment in the short term while the resulting stability would actually boost economies in the long term.